Please Note

There are images on this page that some people may find disturbing or that may trigger memories of trauma.

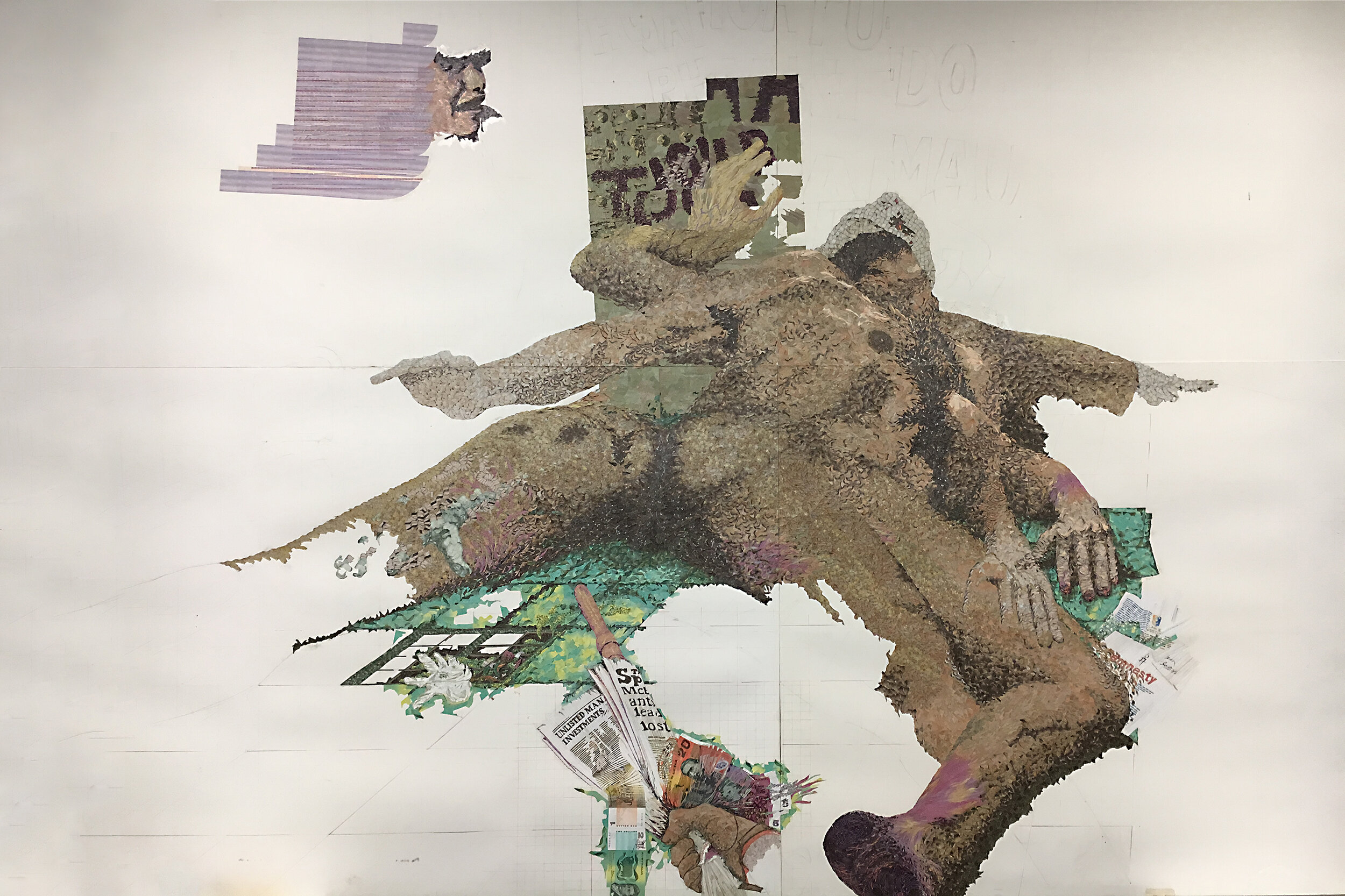

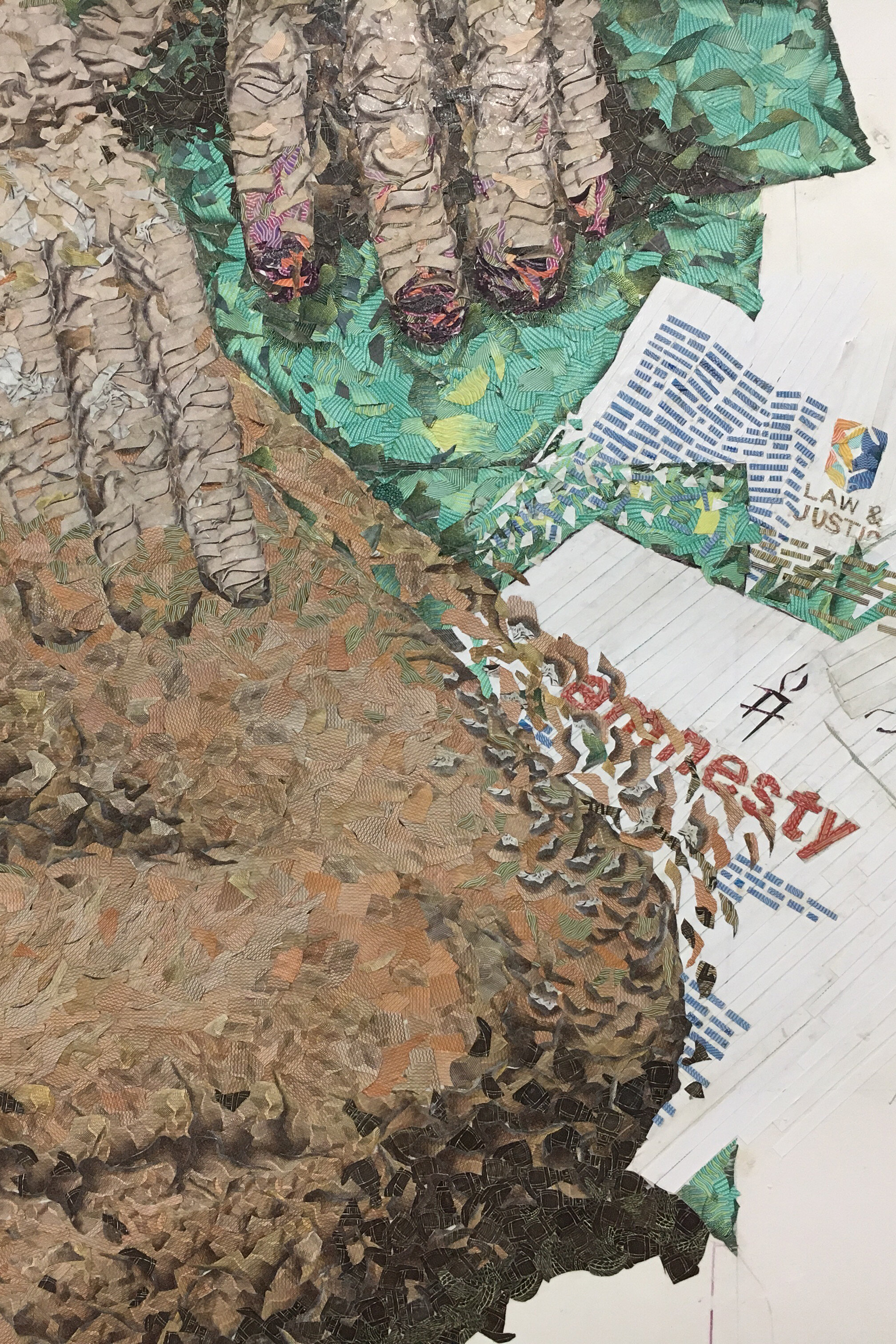

John Reid 'Untitled - Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982 -' (Detail). August 2019. 300 x 500 cm (9 panels bolted 3x3). Australian banknotes, graphite, coloured pencil, glue, board, cedar moulding, metal bolts and production procedures

Untitled: Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982 -

The subject of this artwork is political or enforced disappearances. The work was initiated in 1982 in response to Amnesty International’s ‘Disappearance Campaign’ triggered by the criminal political climate in Central and South America; and the Australian government’s relationship with Indonesia and policy on East Timor.

An enforced disappearance is the abduction of a citizen and the subsequent secret detention, torture, murder and disposal of their body by agents of the State. The victim effectively vanishes. Usually, enforced disappearances are inflicted by governments to suppress popular opposition to repressive economic policies maintained through military aid from foreign governments who are accomplices in the economic exploitation so as to support affluent living standards in their own countries.

The intent of the artwork is to appeal for ethical vigilance against Australian government foreign policies that are fuelled by greed. The conceptual relationship between the artwork’s focus on economic exploitation and its medium of money serves to visually dramatise the intent; and to attract scrutiny of it by the State and subsequently the media. From 1984 to 1987, the artwork was legally contested which enhanced its impact.

Untitled is a process artwork. Its exhibition is performative and, in addition to the presentation of the collage, includes the creative procedures of its production in the gallery space. There is no point in time when the work might be considered complete. Authorship is trans-generational. Custodial responsibility for the artwork and permission to work/rework its surface passes from one artist to another.

John Reid Untitled - Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982 - (Detail). August 2019

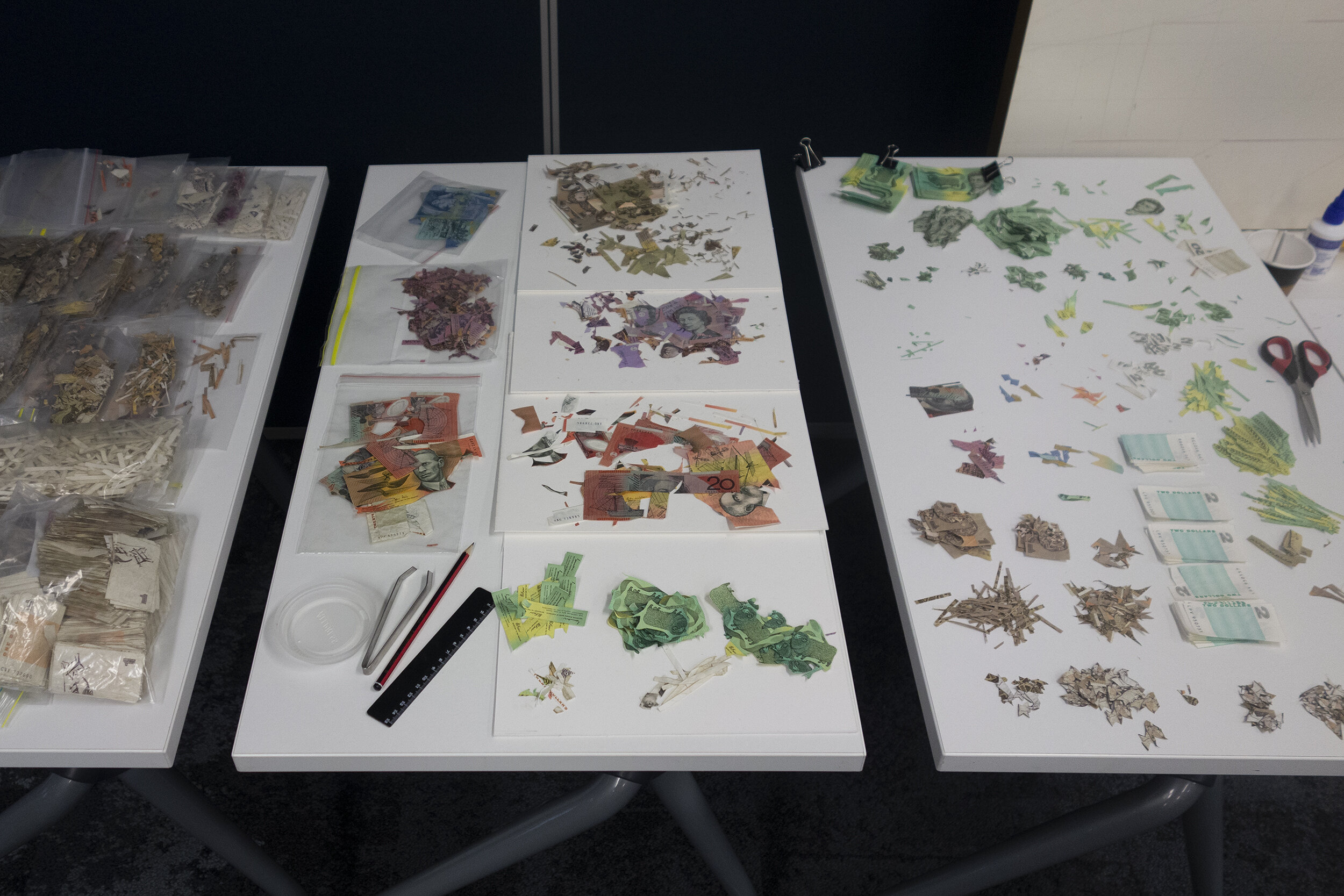

John Reid Untitled - Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982 - (Detail). December 2019

Above: Cut banknotes ready for application to the collage surface. December 2019

Right: Artist-in-Residence studio space, Southern Cross University, December 2019.

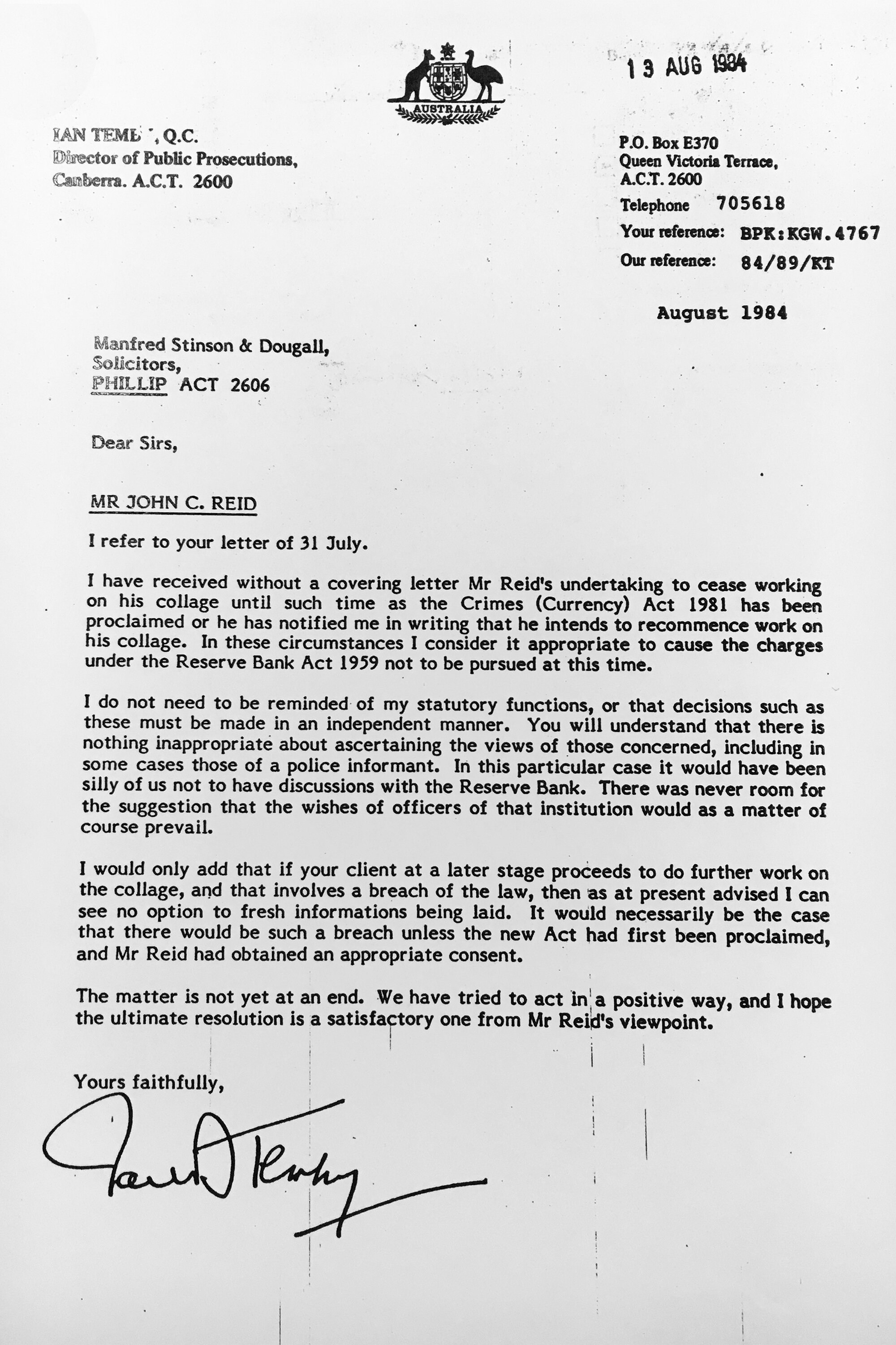

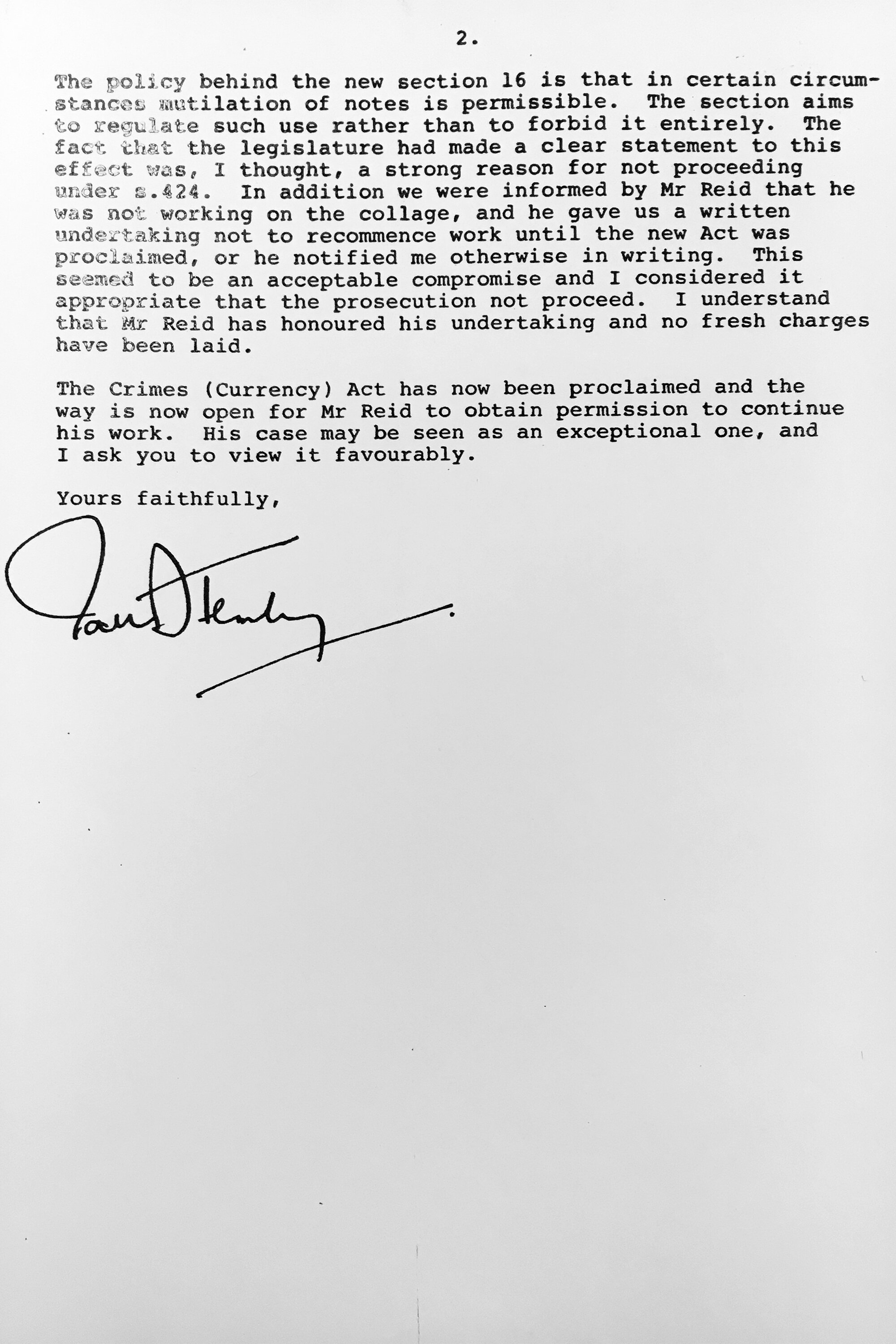

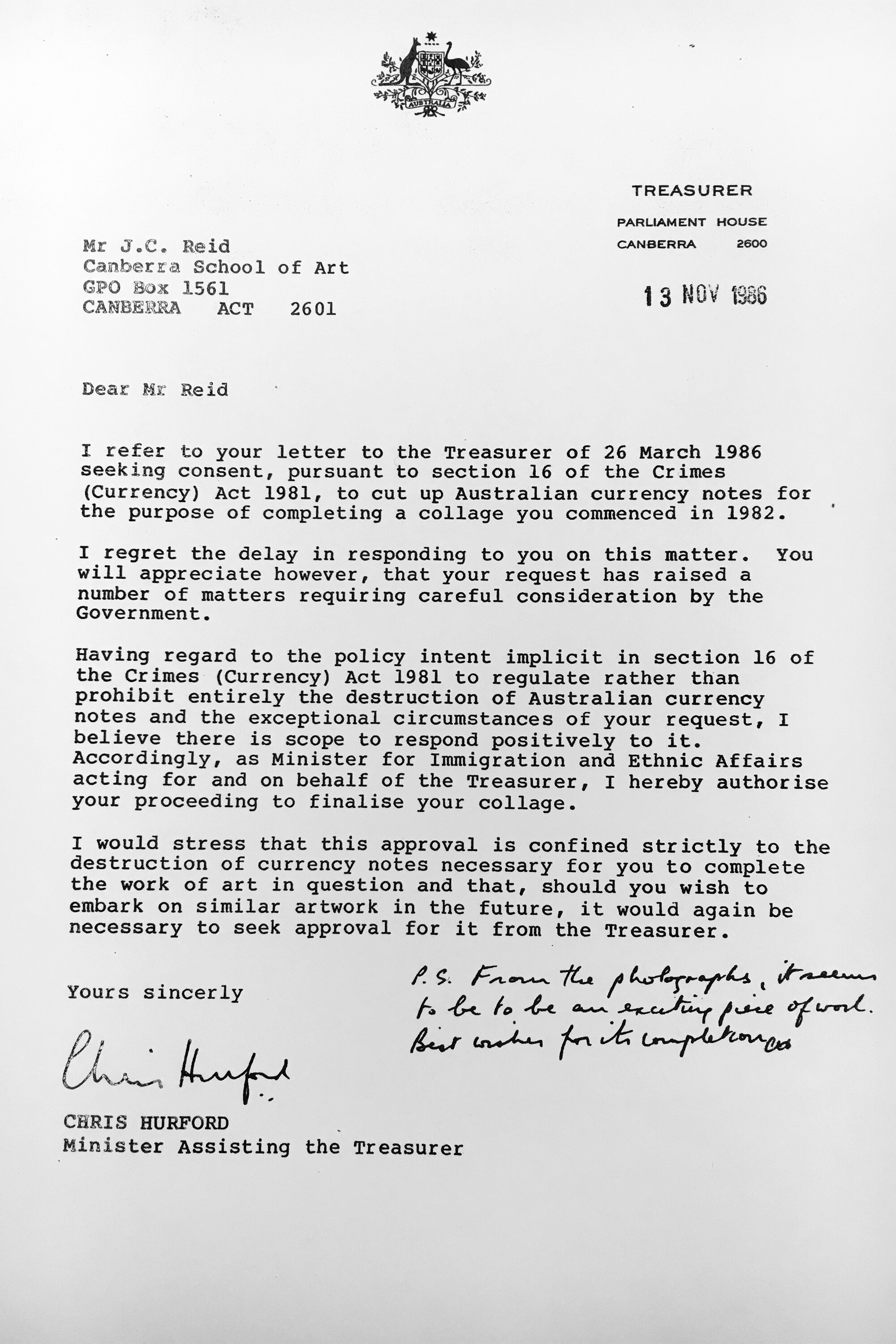

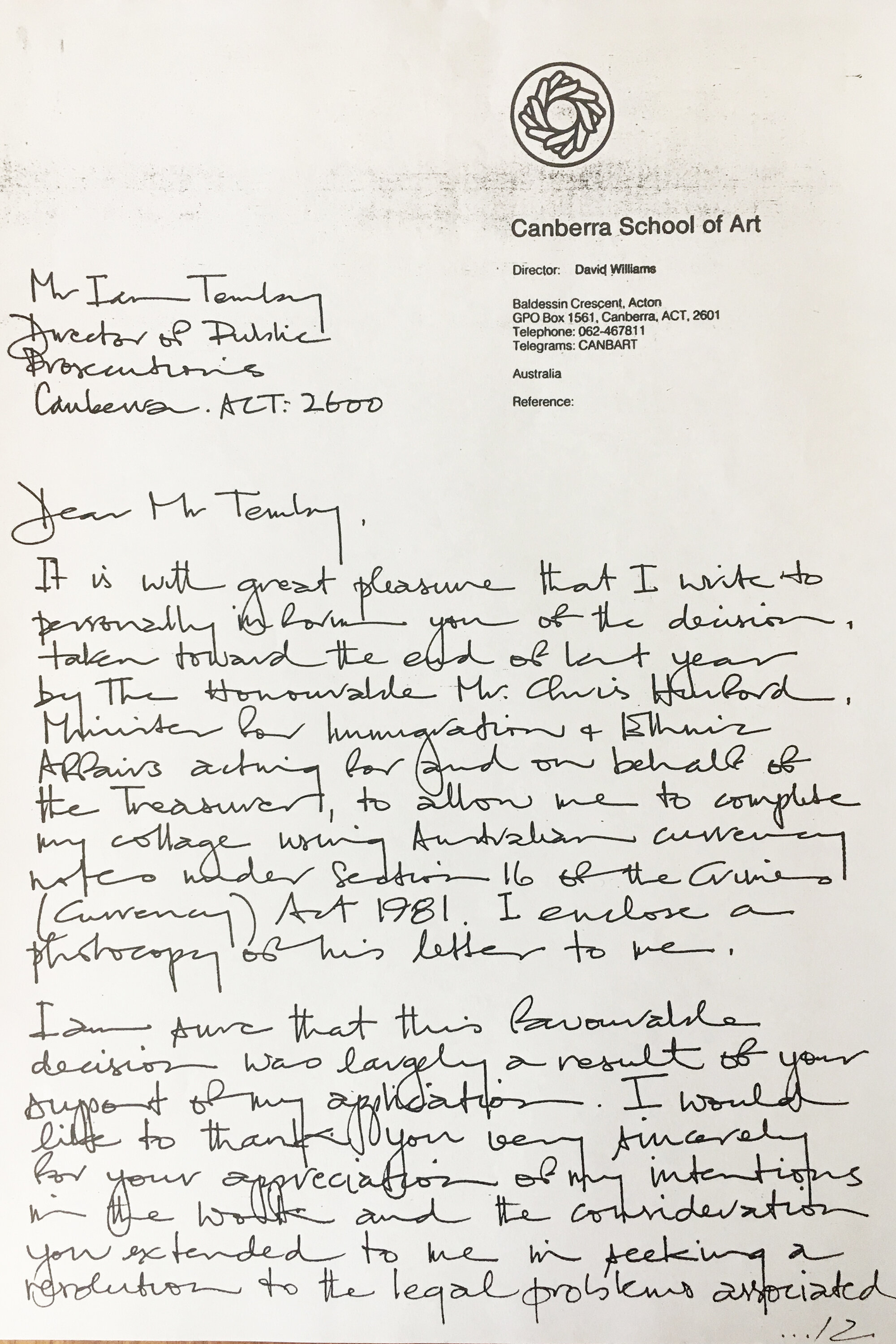

Untitled: Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982 - : Legal Dispute 1984-7

Untitled: Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982 - : Legal Dispute 1984-7

On February 1, 1984, I was contacted by the Fraud Squad, Australian Federal Police, about a Canberra School of Art envelope sent to them (in October 1983) containing 52 mutilated Australian $1 banknotes. My name was written on the envelope. "Do you know anything about this?" A policeman enquired. "It's consistent with what I'm doing for an artwork", I responded. "Did you cut these notes"? He asked. 'I’m not sure I cut the notes you have, but I am cutting up banknotes". "Can I come and have a look at what you are doing?" We made a date that afternoon.

Two Fraud Squad officers duly arrived and we sat initially in my office at the School. I explained in detail what I was doing, and why. I didn't hold back on the 'why' bit in my account. Their eyes were starting to glaze over so I suggested we proceed to the studio where I was undertaking the work. I imagined that they imagined that I was doing some type of paper Mache work. When they entered the studio and saw the scale of the undertaking - a partly collaged 3x5 metre surface mounted on the wall in front of a table with a couple of thousand dismembered banknotes in neat piles surrounding a pot of glue, brushes and scissors - they came back to life and withdrew mobile phones like pistols from holsters in a western movie. Within 20 minutes the studio was crawling with members of the scientific squad with gloves, tweezers and cellophane packets confiscating my art materials. A young officer, in Jimmy Olsen press-photographer style, took photographs of the partially constructed body of the political prisoner i was rendering on the mural surface.

The AFP Fraud Squad assault on my studio at the School of Art culminated in 52 charges being laid against me, but not before a considerable amount of electronic and press coverage of the incident. The raid made the evening national news on ABC Television. Before any interviews took place, I sought a commitment with journalists involved that they must address the subject matter of the collage in their report - namely political disappearances and the monetary greed that underpinned their perpetration as an insidious form of mass repression to quell protest over economic exploitation. With the several interviews I subsequently did, this agreement was not breached. The mass media interest was so successful in bringing political disappearances to the attention of the Australian public, it established a strategy that I was to use effectively (although there were some failures) up until the advent of social media. To accelerate the otherwise slow gallery-based fine art discourse, I flirted with the law to attract the interest of journalists (always hungry for stories with visual supporting material) to move my artwork into the mass media - most desirable as 'news’.

The documents below have been selected to provide an overview as to how the legal saga unfolded and was ultimately resolved.

Essay: Terror - Lest we forget

The essay, Terror. Lest we forget, was written in mid-1999 on the occasion of, and in response to, a visit by Professor Michael Taussig, Columbia University, USA, to The Australian National University in the same year.

Above: Collage visual aid. Photograph: Hanh Tran

Terror. Lest we forget

John Reid

Knowledge of political disappearances emerged for me from the crudely inked pages of Amnesty International's printed material in 1981. The phenomenon struck me as an alarmingly virulent form of terror, of repression. It was a blow not to the viscera, the more familiar location of shock from accounts of horror, but to the intellect. Something to be said for the editorial treatment.

The terrorist who I had previously defeated in my mind because of his or her inability to discern the enemy had now become astute – the enemy is who ever terror kills. The terrorist who I had defeated in my mind because of his or her meagre and make-shift resources now had sanctioned access to the arsenal of the state. The terrorist with whom I could conceivably argue because of the conspicuous nature of ideological passion now becomes anyone whose capacity for sadism and murder is the primary form of expression. This grim human urge surfaces in many countries with impunity and compounds in magnitude in like minded company. The terrorist becomes the system, a grotesque hydra, a pack of paramilitary thugs for every suburban block.

I resolved to deal with my anxiety by making a picture. Visual image making is my chosen medium of expression. I would need help to extirpate this monster. The picture could work for me in the recruitment of allies. Work like vaccination, a serum for my community. Work even when I'm dead and protect my children. A fascist squad requires a thousand hands to stop its deadly momentum.

A picture about disappearance can be fixed to a wall. Each mark (disappearances always leave marks) can be viewed together; collarged with other marks from stairwells, from trucks, from cells, from chambers - thousands upon thousands of them. Should the locus of terror's train emerge in the picture’s overview it may be possible to derail it and thereby exorcise my recurring dream of disappearance:-

I desperately seek the meaning of a word in a huge book. The entry refers me to several synonyms. For the meaning of these, I am referred to several more. And for their meaning, yet several again. I feverishly strike each reference from the page. There is no sanctuary; recto, verso, top, bottom. Every word is an informer. Each one is guilty. Each one disappears from the page under a lashing of ink administered by my pallid hand. The passion eventually dissipates. The inquisition is reduced to routine mindlessness.

My nightmare ends when I realise that I have blacked-out an entire dictionary, except…

One word always remains.

--------------------

Images of atrocities are impressive. Many still accompany me from childhood when I first encountered documentations of declared conflicts. By virtue of family participation in them, these histories had infiltrated our modest library. They were contained in a large bookcase with glazed doors. "Lest We Forget" was embossed on some of them. It was also the phrase that resonated at school each year in the memorial services for Australian soldiers who died in these actions. A potent motif of national consciousness, it served to reinforce the memory of death in all the portrayals of it that I had encountered:- the entrenched victim of war, the crucified Christ as a ghastly image of religion; the criminal, hung, as a perverse consequence of justice.

Artist impressions of ritualistic acts perpetrated against the individual by ancient and alien cultures also shocked my childhood sensibilities. These were secreted in perfect bound volumes of The National Geographic Magazine that were log-jammed into honey coloured blocks on the lower shelves of less elaborate cupboards in our airy Townsville home. Later, as I cruised public library shelves, seemingly more in control of my education, I would compulsively reach for the glossy compendia of more contemporary horrors rendered in scrupulous detail by light sensitive materials. I had experienced the detatchment of the professional photojournalist (lest we forget) some twenty years before. My childhood neighbor and contemporary, Rachel, was hysterical at the prospect of her father decapitating a hen with an axe. Despite the exhibition of her extreme distress as protest, she refused to leave the scene of the execution. If it were to happen, she would watch. (I didn't look. I watched Rachel instead). Rachel was a very attractive girl. Her parents were proud of her appeal.

"Terror as usual” (Taussig. The Nervous System) remained largely invisible to me during my early life in the 50's in Queensland - a state of delusion. The forced separation of Australian Aboriginal children from their parents and their protracted terrorisation at the hand of church and state did not register on my consciousness. What of our collective, grubby business in New Guinea, in Korea? Our bashings and deaths in custody. What else was there?

--------------------

Because of the detached nature of my mental conditioning to terror (and in some other respects in spite of it), I was susceptible to the chilling messages from Amnesty's journal. I knew, somehow, that editorial policy moderated the treatment of terror in the journal. It did not match reality's pathology. A line was always negotiated between a potential reader's outrage at terror's talk and their possible alienation from Amnesty International as a result of the overwhelming horror of the worst of its business. In Amnesty’s public document, the defense of non-violent expression of opinion and the rescue of those incarcerated for it has to be knight-in-shining-armor stuff.

I went to London in 1982 to the archives of Amnesty at its headquarters. I wanted to step on the other side of their editorial line so that I might ultimately draw my own. There were problems with this. My ordinariness combined with my extraordinary interest in what was going on raised the matter of security. There was a hint of suspicion. I was eventually let loose but only in the public section of their library. The information available there was considerable.

I went to Berlin. My engagement in Amnesty's office in the West of the city was confined mainly to the visual. The German campaign posters for the Disappeared had tremendous eye appeal. They were large and colourful; bold mixtures of image and text. I rolled a selection into a manageable cylinder and returned to my hotel room. It was there, staring through a window into a courtyard that resembled a mine shaft, that my process of picture production was settled. I would collage all my money. 'Guernica' came instantly to mind: that sort of scale; that sort of chronicle. My pulse rate quickened. There was a touch of sweat. My body was preparing to escape. I knew I had thought of something worth acting upon.

I returned to my power base. It is a space in the Photomedia Workshop at the Canberra School of Art where I work as a visual artist and teacher. The details of my plan could be summed up in a few words. Convert asserts to Australian bank notes, assorted denominations. Acquire acid free board, cedar moulding. Construct picture surface to accommodate bank notes (3x5m). Acquire scissors, tweezers, brush, glue, pencil, ruler, rubber. Collage bank notes. Compositionally resolve picture by pasting last banknote fragment. Estimated completion date six years hence.

--------------------

As a general proposition it is desirable strategy in the visual arts to establish a relationship between subject matter and medium. Colour as a subject begs paint. Veracity can be well served by photography; the human touch by clay. For political prisoners, it's money. The relationship is a tense one. Chomsky and Herman (Spokesman, 1979) in their two volume treatise on the political economy of human rights had elucidated the pact in words:- Foreign government aid-dollars prop regimes willing to repress their own people so as to maintain the foreign economic exploitation of them.

Not only did I want to visually express this thesis,

$$$>Political Disappearances>$$$$$$$$$

but to incorporate it as a two dimensional image with a slippery surface. The literal mind falters when it encounters a static image with a slippery surface. It's a statement with an illusive grammar. It's visual expression at its best. The optical contemplation of the static image which, if it is indeed slippery, triggers another collage - unanticipated cerebral conjunctions of personal and cultural understanding. The insight liberated by each conceptual slide can further propel the afflicted viewer into direct political action. That's what I wanted. I was confident I could get it because I had had it before.

--------------------

A clear glass jar full of unsealed condoms in a communal lubricant stood on the front steps of a typical suburban Canberra dwelling beside the morning newspaper and bottles of home delivered milk. Such was the image that, in 1969, comprised the pictorial component of a poster advertising the attributes of "family planning". If you were a milkman involved in providing the essentials for life, would you deliver contraceptives? began a passage of text reversed from the photograph. I had designed and produced the poster for publication in the university student press as a deliberate flouting of the law. Advertising of contraceptives was prohibited in five of Australia's six states and this frustrated the communication of services offered by the Family Planning Association. The lead text concluded, Disgusted at the sight of french letters on the doorstep? Oops! That's where children are usually abandoned. The graphic power of the poster image lay in the blatant unmasking of the condom and its visual conjunction with the vessel of pure milk. We made sure the relevant authorities knew of our challenge.

Police action was quick to follow. The student newspaper office and union building were raided. Found copies were confiscated by grumpy detectives. Questions were asked in the national parliament. There was some concern by politicians about the “fraying of the moral fabric”. All of this, plus the provocative poster graphic made good copy for the commercial press. The poster was reproduced in several newspapers and the matter was canvassed nationally. Within six months laws were changed and all states permitted the advertising and display of contraceptives. This was my first experience of the galvanising power a visual image could have in a political process. Like the first time gambler who has a big win, I was hooked even though I knew the real heroes and heroines of the FPA and Amnesty to be their petitioners and letter writers.

--------------------

It's February, 1984. The police forensic photographer photographed the human figure spread eagled on the tiled floor. There was evidence of struggle. A message was drafted on the wall.

Gloved members of the scientific squad silently hovered about taking samples and placing them into plastic specimen bags. The whole operation had taken an hour, perhaps more. It began with a personal interview and ended in a clinical confiscation of the stuff people die for. As the officer in charge pulled out his team he turned to me and said, "Don't remove the picture." He turned again and grabbing the plastic bags left the Art School with my money, cut for application to the picture surface for the depiction of skin.

Some weeks prior to this police action, 52 cut one dollar notes had been taken from my work bench (presumably by a disaffected colleague) and sent in an art school envelope to the federal police. Investigations led two fraud squad detectives to me and I could not resist telling these gentlemen the full story. The defacement of money has anxieties for the state. The principal fear is its fraudulent potential - by an ingenious method of defacement the perpetrator ends up with more negotiable notes than at the outset. Another misgiving (advanced vigorously at the time by the Reserve Bank of Australia) has something to do with the "integrity of the currency". Anthropological field work may be required to get to the bottom of this one. It is curious to realise (as an anthropologist did) that the sample of cut notes sent to the police, selected from dozens of possibilities, had Elizabeth II's face cut out. The image of a faceless queen (the ultimate mask combined with the notion of ultimate power) would strike a certain fear into the hearts of her majesty's servants.

So successful did police involvement prove to be in my enterprise of collaging banknotes to address the matter of political disappearances, that many of my art school companions suspected I had turned myself in. The ensuing charges and courtroom posturing lasted for almost three years and attracted considerable mass media attention. I collaborated with journalists to address not only my defacement of currency and the reason for it but also to make the connection that economic exploitation had with the perpetration of political disappearances. The electronic and print media came to my aid in attempting to prick the conscience of the affluent who might still value the idea of a non-violent society and who could liberate their resources to help alleviate human suffering instigated by greed and megalomania.

The enemy can be subverted anywhere in the world on the stock and information exchange.

--------------------

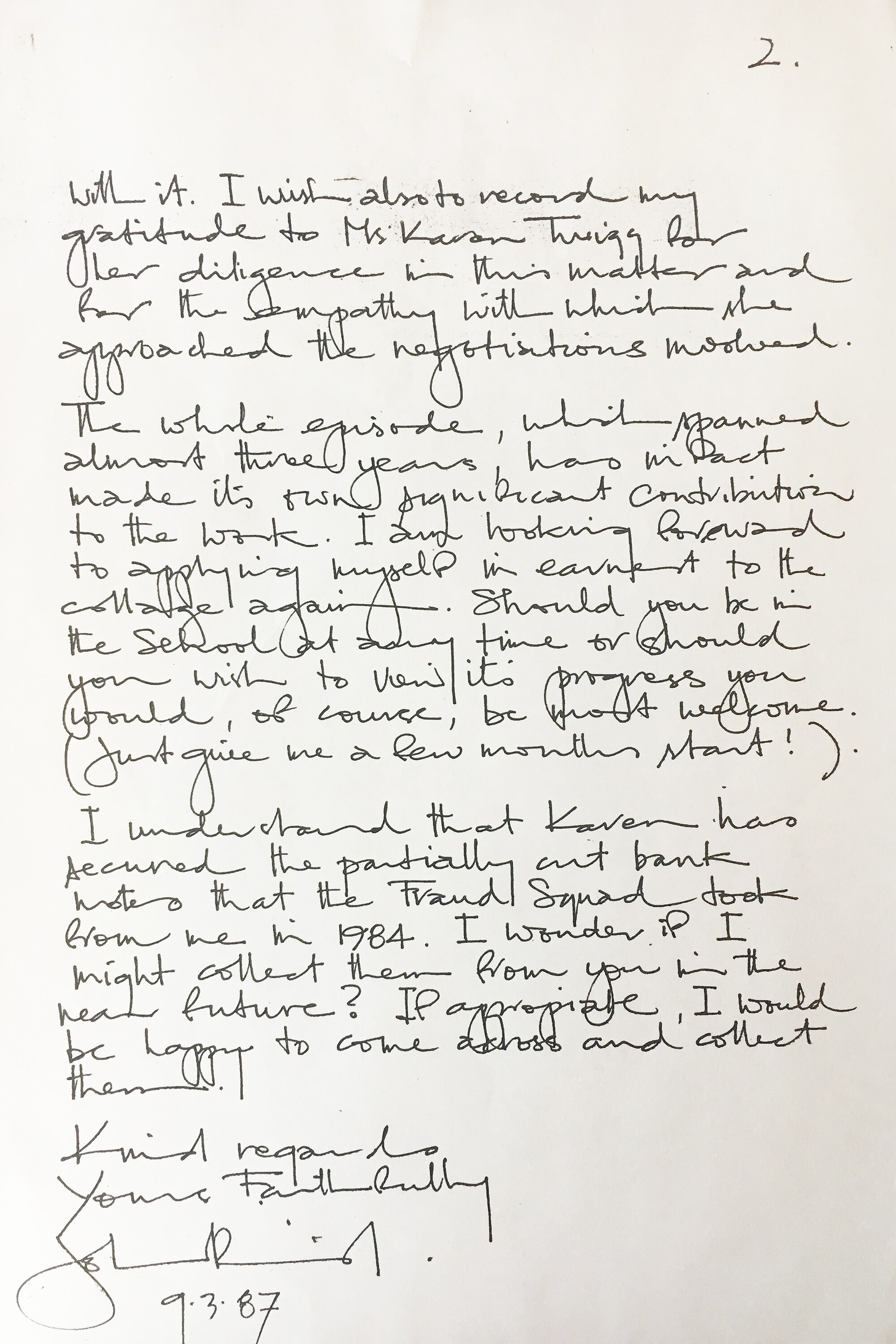

The paper-money image of a universal political prisoner has now occupied my studio wall for 15 years. The artwork of which it is part is still embryonic and there are thousands of bank note pieces waiting to be assembled into a visually engaging whole; into a slippery surface. My valuable collage materials have been returned from the clutches of the police by virtue of the intervention of the Federal Director of Public Prosecutions. In what turned out to be a collective enterprise of good will for the sake of art on the part of government and its instrumentalities, I avoided prosecution. I was granted immunity from future prosecution as a cutter of Australian bank notes for the purpose of collaging this particular work.

The advice I was given by my accountant many years ago, "Cut up the smaller denominations first", has justified the fee I paid for it. The Taxation Department no longer queries the deduction I claim from my tax for the money I cut up as art material. Now, the original decimal paper currency is progressively being replaced by a more counterfeit resistant variety. I have had to stockpile the original notes. For this, my capacity is limited. These banknotes were/are quite possibly the most visually detailed and vibrant pieces of paper commonly available. The eye-appeal of the collarge is largely attributable to these beautiful engravings being the raw material from which it is composed. There is an increasing imperative to return to a bed in the back of a Valiant Safari station wagon to save rent and liberate more money for the collarge. That's where I was sleeping, in the car park outside the Art School, at the beginning of the enterprise and for the same reason. It was there that I had my first dream of disappearance. The word that is always left at the end of the dream, when I have defaced the dictionary is, I suspect, the word with which I started.

Annual reports from Amnesty continue to document the occurrence of political disappearances in many countries. In its 1999 Report, Amnesty records disappearances - most often secret incarceration, torture and murder - in 37 countries.

The money collage and its subject of political disappearances has 15 years of intermittent work remaining. I have an unclear vision of it as a resolved work which augurs well for a final 'slippery' finish. If it is worth looking at, the work should hang, I think, in a public space. A place where the fate of individuals interface with the machinations of the state, perhaps a parliament house foyer, a legislative assembly or a court of law.

Fortunately, the process of production has itself been a statement on the subject. It is largely an undertaking of intuitive anxiety; a response to highly processed information that carries terror's touch. It has reached over the distance of time and space that prevails between my primary life experiences (here) and the people who have been primarily affected by this insidious tactic of repression (there). When you confront highly processed terror you do so with a measure of relief. You are glad, for the moment, that terror has not grasped your throat. You are like the soldier who must cope with the mixture of grief and elation in that it was a comrade who took the bullet.

I don't intend to wait for terror to come. The price of vigilance is whatever you can pay.

Excerpts

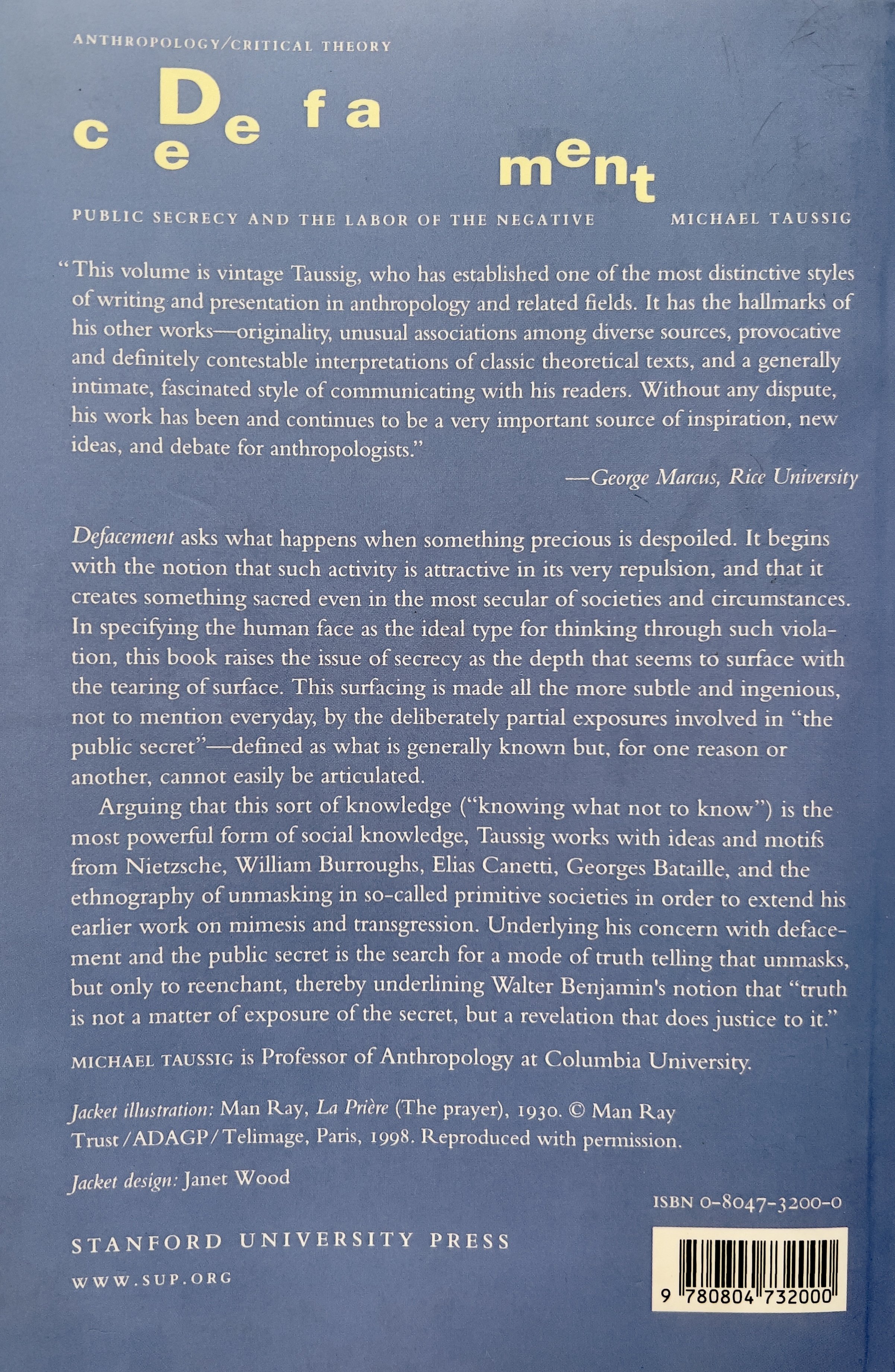

Michael T Taussig DEFACEMENT Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative

Sanford University Press 1999

References to Untitled. Collage of Australian Banknotes 1982-

and

Fishman of SE Australia